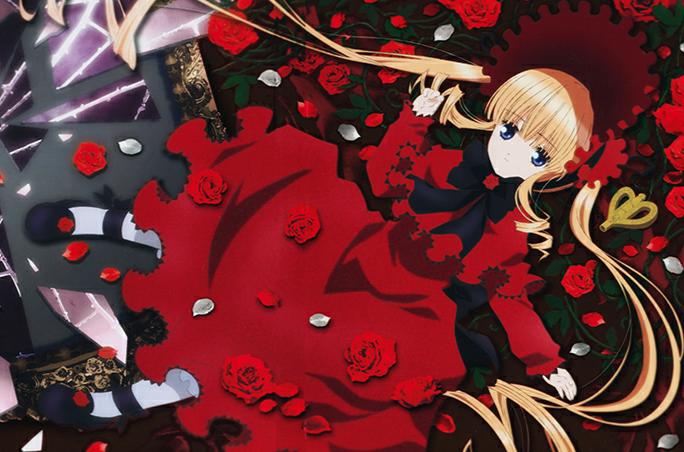

Rozen Maiden – The Doll’s Heart, Eternal Pain: A Gothic Fairy Tale of Existence and Love

[Opening: A Blood-Stained Fairy Tale]

On a certain night in 2004, when the porcelain dolls in PEACH-PIT’s manga first opened their glass-bead eyes, no one expected this Gothic-laced fairy tale to become a psychological shadow and aesthetic awakening for a generation. Rozen Maiden weaves a cruel allegory about the meaning of existence with Victorian lace and shadows—when abandoned dolls yearn to become “real girls,” are they fighting for their creator’s love, or proof of their own being?

[Core Analysis: The Dark Philosophy of the Alice Game]

1. Dolls vs. Humanity: Who is More “Perfect”?

- Shinku’s pride and fragility, Suigintou’s obsession and loneliness, Suiseiseki’s tenderness and envy—each Rozen Maiden embodies an extreme reflection of human emotion.

- Ironically, these dolls, who strive to become “Alice” (the perfect girl), feel more alive than most humans. They weep, hate, and gamble their eternal lives for a single word of validation—a contradiction that makes the story profoundly moving.

2. Media Metaphor: The Complicity of the Dollmaker and the Audience

- The protagonist, Jun Sakurada, isn’t just an otaku by accident. When he intervenes in the dolls’ fate by winding their keys, isn’t the audience also “keeping” these virtual characters alive through their screens?

- The 2013 reboot, Rozen Maiden: Zurückspulen, even introduces parallel worlds, suggesting that choosing not to interact is its own form of violence—a commentary on observer responsibility that elevates the story beyond a simple dark fairy tale.

3. The Narrative Violence of Gothic Aesthetics

- Shattered teacups, withered roses, the click-clack of porcelain joints… PEACH-PIT constructs a prison of frozen time through these motifs.

- The most haunting scene? Suigintou’s birth: her broken body crawling from a trash heap, wings fused from feathers and filth—a breathtaking declaration of revenge for the abandoned.

[Cultural Phenomenon: Why Are We Obsessed with “Painful Moe”?]

Rozen Maiden popularized “itami moe” (painful cuteness), a worship of fragile beauty.

- Social Reflection: Post-bubble Japan replaced 80s extravagance with an appreciation for imperfection—the dolls’ endless battle mirrors modern societal struggles.

- Explosion of Fan Works: The NicoNico era spawned derivative songs like “The Daughter of Evil”, pushing the tragedy to even darker extremes (e.g., Kagamine Rin’s “Tainted Paradise” as Suigintou’s anthem).

[Comparative Analysis: Dolls vs. Other Non-Human Protagonists]

| Series | Core Theme | Aesthetic Style |

|---|---|---|

| Rozen Maiden | Existential dread of the created | Gothic Lolita |

| CLAMP School Detectives | Androids seeking humanity | Dreamlike shoujo |

| Chobits | Love between AI and humans | Cyberpunk moe |

[Closing: Even Clockwork Winds Down]

When the ED “Transparent Shelter” plays in Traumend, the dolls who never became Alice still wait for their father in an endless cycle. This “eternal incompleteness” is Rozen Maiden’s cruelest yet kindest farewell—perhaps true perfection lies in the pain we willingly embrace.

(Suggested visuals: Shinku’s contract with Jun / Suigintou’s iconic black wings / fan-art of “Rose Torture” themes.)